INTERVIEW: GOING PLACES WITH HERB ALPERT

Herb Alpert will have a 10-day residency at The Carlyle from May 31 to June 11. In honor of this, we’re republishing this 2015 interview.

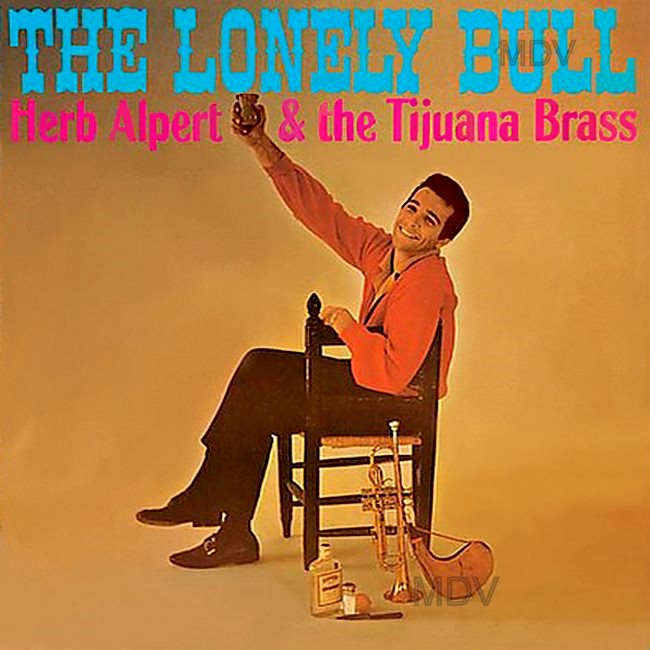

Not long ago, I was walking down a street in Brooklyn and noticed a local resident had set out a few items on the curb. Front and center was a vinyl LP with a cover that instantly returned me to my childhood. It was Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Going Places, released in 1965 when I was 9 years old and nearing the height of my first full-blown musical infatuation. Ever since my mother first popped the Tijuana Brass’s debut LP The Lonely Bull onto the family Victrola, I’d been hooked. Going Places was a high point, not only because the song “Tijuana Taxi” seemed to crystallize the band’s sound as nothing before, but also because the album’s title captured the essence of the whole Tijuana Brass experience—music as a means to travel through time and space.

Herb Alpert is an under-recognized godfather of the “world music” era. First, he made Mexico present and interesting to mainstream America. Then, with his label A&M Records, he gave us the Baja Marimba Band and Sergio Mendes and Brazil 66, the first Brazilian music many Americans—including this one—ever heard. (By the way, Mendes was nominated for a Grammy this year, edged out in the end by Benin’s Angelique Kidjo.)

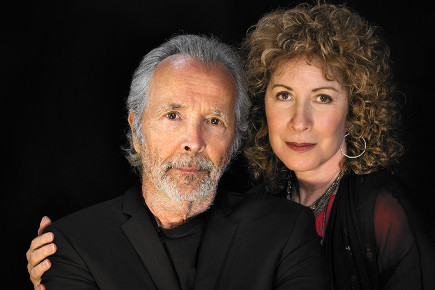

Alpert has remained active in many spheres. His 2013 album Steppin’ Out won a Grammy for Best Pop Instrumental album, and he’s about to release a new one, In The Mood, a collaboration with his vocalist wife Lani Hall. They kick off a spring tour to promote the album with shows at New York’s Café Carlyle (March 10-21; more dates at the end of this interview). Alpert is also a visual artist, and an exhibition of his sculptures, Harmonic Rhythms, opens at the ACA on Feb. 19.

I spoke with Alpert about all this and more by phone from his home in Malibu on Feb. 11. Here’s our conversation.

Banning Eyre: Herb, great to talk with you. How are you?

Herb Alpert: Pretty good. Where are you?

In Brooklyn.

Oh, man. Pretty cold out there?

It’s cold. But we’re below the snow zone. So we haven’t gotten buried like places up north.

Well, it’s only 84 here.

Nice. Well, luckily we’re used to this weather. I don’t know whether you’ve heard you heard our radio program Afropop Worldwide…

I might’ve heard it now and then. Not on a regular basis.

We’re not currently on the air in L.A., but we’ve been syndicated around the country since 1988. And I have to say that my own journey with international music really started with you, and what really strikes me when I think back to that time is how those early recordings really established in my imagination a sense of place. When I heard “The Lonely Bull,” it took me somewhere. My mother loved Mexico and she talked about the excitement of the bullfight ring and such things, and that song evoked this whole world for me. It showed me that music can really take you places.

Absolutely. You hit the nail on the head. Because when “The Lonely Bull” came out, three days after its release it was known internationally. We were getting calls. That was our first release on A&M records. And we were getting calls from distributors all over the world wanting to distribute the record. And when the record finally hit the top 10, I got a letter from a lady in Germany thanking me for taking her on a vicarious trip to Tijuana.

Exactly.

When I first read that, I have a little bit of a chuckle, and then I thought about it. I said, “Man, that record had images that transported people.” So I tried to make that kind of music from that point on. Visual music.

It’s a very striking quality of those records, and it started me on a long journey that’s still going on. So first off, thanks for that.

I’m interested in the way you have reinvented yourself over the years. I’ve just been listening to your most recent records. Steppin’ Out has a new version of “The Lonely Bull” and on the newest record, In The Mood, you revisit another TJB chestnut, “Spanish Harlem.” What made you go back to these songs?

Well, “The Lonely Bull” was a reflection of A&M’s 50th anniversary. I wanted to just take another look at “The Lonely Bull” and present it in a little different way. That’s what I try to do with all the songs that I choose to record. If it’s a standard song, a song that people recognize, I try to do it in a way they haven’t heard before. That’s a pursuit of mine for sure, something I enjoy. And I do it for my own pleasure. I feel if I can have fun playing, there’ll be a certain amount of people that might have fun listening.

A good bet. And “Spanish Harlem,” a similar story?

Yeah. “Spanish Harlem” was just presented to me by one of the members of my group. They had an unusual way to approach it. It appealed to me. It’s a melody that striking, an unusual melody, and I just felt like I could bring something different to it again.

I like what you did. I’m curious about your performing live these days. You just said that you do recordings for fun. What about performing? Do you still get a kick out of playing live shows?

Well, I certainly wouldn’t be doing it if I didn’t enjoy it. We have a tremendous group behind us. Three musicians. The group is very transparent, what we’re doing. We just have bass drums and keyboard behind us. Obviously, my wife Lani is a world-class singer. She was the original singer with Sergio Mendes and Brazil 66. By the way, it’s Sergio’s birthday today.

Is that right? Nice.

I get energy from playing. I get energy from hearing a response from an audience. It’s something that’s just part of me. I started playing the trumpet when I was 8. I practice every day. And I enjoy it. I enjoy the process. I know I’ve been extremely fortunate to have so many records. Seventy-two or 73 million records sold.

Wow.

I feel like at this point in my life if I can make people happy playing the music that I enjoy playing, I think I need to do that.

Listening to the new records, I find your tone is exactly as it was.

Actually I think I’m playing better. I’m getting more out of the trumpet with less effort than I did 20 years ago. I guess that just comes with age.

When I was a kid I wanted to play trumpet, like you, but I was convinced to start with trombone. My teacher told me that you were not necessarily the best model, in terms of technique. That told me something about style and taste, something that has stayed with me. The musicians I love most—it’s not that they’re always technically brilliant or can manage complicated harmony. It’s really about personality and character. And that’s what I still hear in your playing, your character.

Well, that’s what a lot of people don’t understand when they try to analyze art, they get a little bit too close when they’re trying to make sense out of it. It goes back to what Duke Ellington or one of those greats said: It ain’t what you do, it’s how you do it. The biggest accomplishment you can find as an artist, whether you’re a painter or a sculpture or a musician, is to find your own voice. If you can find that, then you can express yourself honestly. You don’t have to worry about does it sound like Miles Davis or Louis Armstrong or Harry James or any of the greats.

Amen. Back to performances, how many gigs do you play a year?

I don’t have it broken down that way. It’s a significant amount. This June, we’re going to start playing with a symphony orchestra and see how that feels. After we play the Carlyle, we have a few gigs after that on the East Coast. Then we’re taking a trip to Japan, to play for a week at the Blue Note in Tokyo. I don’t know. I’m just having a really good time. My wife and I, we’ve been married 41 years. We love performing together. I’m not crazy about traveling and packing and unpacking. That’s not one of my favorite things to do.

I can imagine.

But I like to play because the way I have it set up with the group, it’s very spontaneous. We do a medley of the Tijuana Brass. And Lani will sing a medley of things she did with Sergio and Brazil 66. But other than that, it’s all impromptu. Whatever we do on one night, the next night it will be totally different in terms of the songs that we choose to play. So it’s always: pay attention and have a good time and see what you can create tonight. That type of feeling.

I’m really looking forward to hearing you next month. I also have to ask you about your painting and sculpting career, which I don’t know a whole lot about.

Well, I’ve been painting for over 40 years. In the ‘60s, when I was traveling with the Tijuana Brass, we were going to various cities around the world. I used to go into those great museums, and I would kind of gravitate towards the modern art section. And I might see a painting that was black with a purple dot, or a purple painting with a black dot. And I’d think, “Man, I’d like to try doing something like that.” So I bought some canvases and started moving paint around and had fun doing it. My first paintings looked like, you know, the way an elephant or a monkey paints, just sort of spreading colors around. But I had a good time, and I just kept at it because it was fun.

About four or five years after I started painting, I got great comments from some gallery owners here in Los Angeles, and I started showing my work. It caught me off guard. I wasn’t planning on doing that. And then I got into sculpting, which the ACA gallery in Manhattan is going to be showing, my sculptures, midsize sculptures. Now, I’m sculpting like 18 footers. There is no room in the gallery for that.

You know, I’m a right brain guy. I lived most of my life painting and sculpting and playing the instrument. Certainly I do a lot of good work with the Herb Alpert Foundation. I’m very fortunate. And like I said earlier, I like to pass on this gift that I have of making music that makes some people happy. I like to spread some joy. I think we can use that in this strange world of ours at the moment.

I want to ask you about world music. We at Afropop have kind of lived through the “world music era,” which has been an interesting and kind of strange experience. It’s brought so many people to a greater awareness of the world, focusing on the culture and humanity of places, rather than what we see on the news. But at the same time, in the terms of the industry, it’s been kind of a ghetto. Artists have been frustrated at being tagged as “world music.” It’s not the way they would self-identify. But I wonder what your experience of all this has been: Have you listened to much of this music? Are there artists that have touched you? Because I think you’re really an important part of the genealogy of this whole phenomenon, so I wonder what your experience has been during these years.

Oh yeah, it’s been profound. I mean, because of the Internet especially, the last several years. Music is all getting together. You know, I’m part of the UCLA Herb Alpert School of music at UCLA. And we have probably the greatest ethnomusicology department in the world, and it brings all this music together. I had my first taste of it with Sergio and Brazil 66. Then I had a group with Hugh Masekela and we traveled around listening to that type of music and experiencing the music that was coming out of Africa with Fela and all that. It all kind of gets together. It’s a jumbo. A gumbo. It’s something that we’re all going to be borrowing from.

I mean we certainly did that. There’s nothing really new in music. There’s 12 notes that we’re all playing. And it can be scrambled up in lots of different ways. Gerry Mulligan, the great jazzer, was a dear friend of mine. He recorded for A&M, and he would give his credit to Bach and all the great classical artists, because he was deep into contrapuntal music, and that’s where it started.

That’s beautiful. I’m glad you worked with Hugh. What a guy.

Oh yeah. That was a real eye-opener. And the trombone player, Jonas Gwangwa—I mean, this guy sounded like a wild elephant in the jungle. He was sensational. I’d listen to him every night and it was beautiful.

We know the UCLA program. We’ve worked quite a bit with A.J. Racy who does Arabic and Middle Eastern music there. For the last 10 years or so, Afropop has been producing a series called Hip Deep. Basically we work with ethnomusicologists, historians and other kinds of humanities scholars, and use music to tell bigger stories. Music becomes an entrée into history, politics, religion, and so on. So we go from that visceral transportation experience to get into culture and history.

You mentioned Fela Kuti. So how is it that this funky, James Brown music that gets transformed in this whole new way and becomes Afrobeat that goes all over the world? Well, the music itself becomes a kind of encoded history that tells you the answer. You can really learn through music why the world is the way it is. I know you’ve done a lot of work with music education, and I wonder if this kind of indirect learning figures into your vision.

Oh, it absolutely does. I think the most beautiful part of it is that music and art are something that you can’t explain. I can’t explain why I like a Louis Armstrong solo—and I love Louis. Or Miles Davis, or Clifford Brown, or Charlie Parker. Or Jackson Pollock. Any of the great artists. There’s no way you can explain it. Once you try to analyze it, what the motivation was. Was he stoned or not? It’s not important. The question is does it hit with you. And people who don’t get the arts or have a bunch of talent, but they don’t how to express it because they start analyzing it too deeply. I mean, I walked out of the Sistine Chapel in the ‘60s thinking to myself, “Man, I can’t paint. Did you see what he just did? Michelangelo? It’s otherworldly. What am I doing?”

And then as soon as I got over that hump—and it took a while—I started being myself. I just expressed myself the way it comes out. Leave it at that. I guess my point was that if you try to analyze art too closely, you can lose the essence of it and the mystery of it. That’s the thing that motivates it.

I take your point, and I suppose we may have been guilty at times of overly explaining things. But one of the reasons we get there is because we’re mindful of the struggles African musicians have faced. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the time when independence was sweeping the continent, these artists were trying to figure out how to reclaim a sense of identity after this tumultuous experience of colonialism. A lot of it was about going back to traditions and reinventing them, to give them dignity after having been stigmatized under colonial powers. They created some of the most beautiful music ever in my opinion. Nowadays, there’s a dialogue going on about how young musicians are losing that link to the old culture. A lot of the old guard feels that they are.

You know, sometimes I think it’s in the DNA as well. You know my father was from Russia. And sometimes I listen to myself and say, “You know I’ve got this kind of sad-optimistic feeling that’s coming out.” I don’t know. It’s just there.

I love the DNA idea. I think one of the reasons that so much music from Mali and Senegal and Nigeria are so big here is because those cultures are in our musical DNA. Literally. Those are the people who came to New Orleans and the Carolinas and helped create our music.

Absolutely. People talk about Jobim. He was a genius, of course. People say his roots are African. His roots are this or that. But it’s really not important. Just listen to what he’s doing. You can probably conjure up a lot of reasons why he writes the way he does. But in the final analysis… I’m probably saying something different than what you would like to hear. But who cares?

Not at all. Whatever forces of history are running through an artist’s life, it’s ultimately the power of expression and the genius of the individual that sells the deal, right?

Well, you can certainly analyze to a degree what he was doing, because he wrote these rather simple type melodies with this extraordinary harmonic structure. Yeah. Now what? That’s what he did. Try it.

I have. I know. Very difficult! We’ll listen, it’s very nice to talk with you. I really appreciate your taking the time.

I enjoyed speaking with you as well. You’re on a nice track it sounds like.

We’ll see you in New York, and we’ll try not to have a big snowstorm when you come.

Oh, please. I can’t use it. I’m from the West Coast and I’m spoiled. Man, we played a couple months ago in Montana, in Bozeman Montana. After the concert we came outside. It was like 7 degrees. I couldn’t believe it. I never felt anything like that before.

As I say, we’ll try not to do that to you.

OK, man. Nice talking. Good luck